Pretoria Pit Disaster

Pretoria Pit Disaster

During the Christmas week of 1910, the task of most families in the Westhoughton and Atherton area was to prepare for the upcoming holidays. However, the local coal mining families were completely unaware that in a brief instant their lives were about to be tragically, and irrevocably changed.

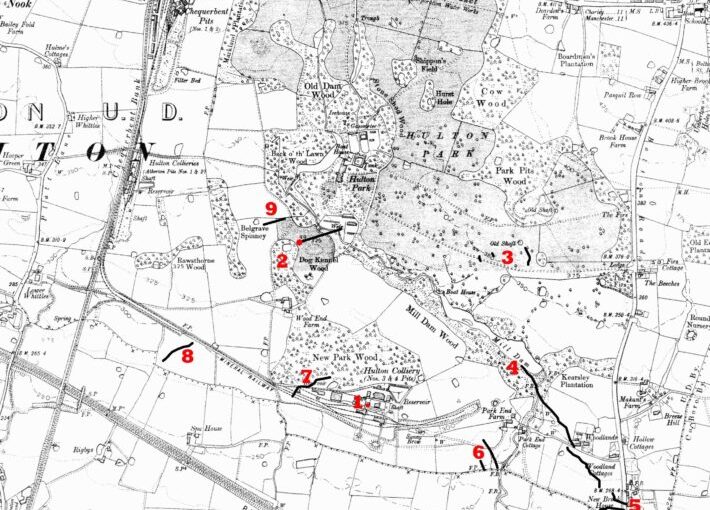

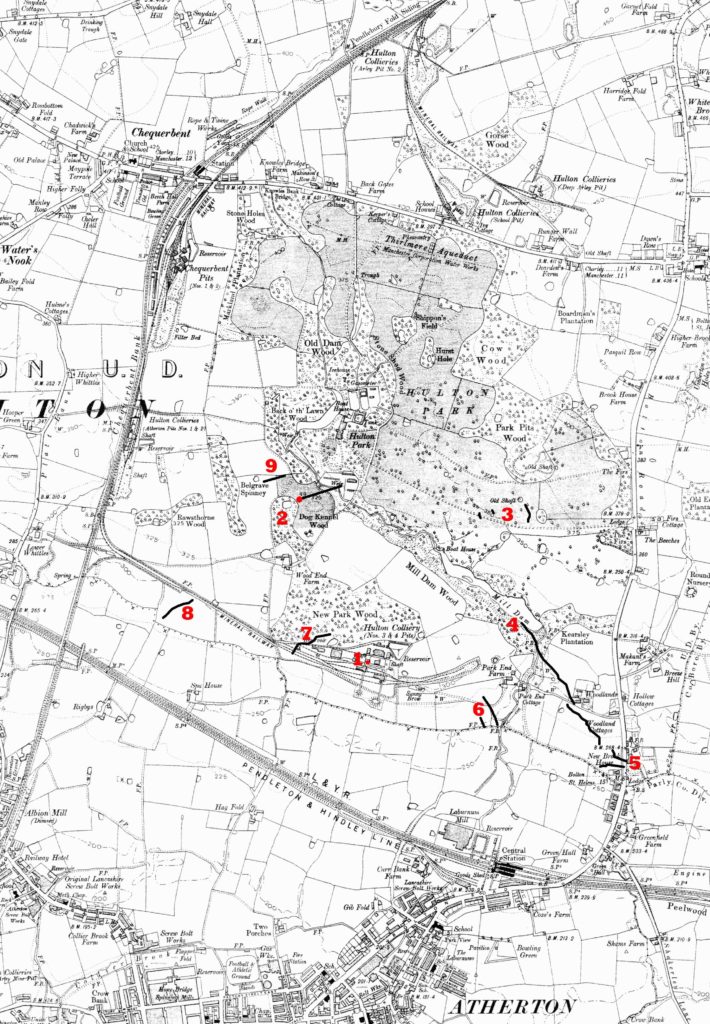

The Pretoria Pit Disaster is the worst coal mining accident to have occurred in Lancashire, and the third-worst mining disaster in British history. The Pretoria Pit was a complex of coal mines owned by the Hulton Colliery Company and situated on the border of Westhoughton and Atherton. Pretoria Pit was the largest coal mine in the Westhoughton area, working five coal seams in the region. Each seam had its own mine: Trencherbone, Plodder, Yard, Three-Quarter, and Arley mine.

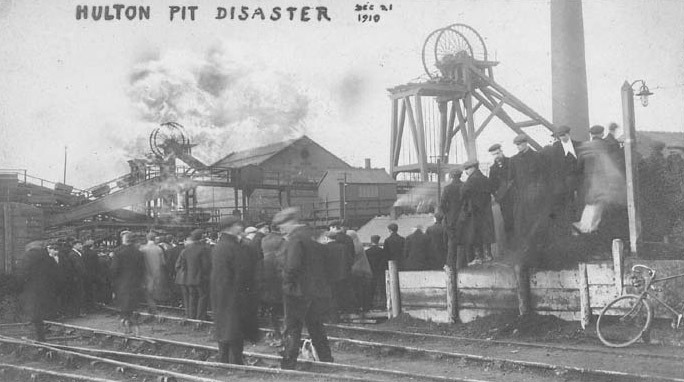

The Hulton Colliery Co. employed approximately 2,500 people locally. On the morning of December 21, 1910, a total of 898 men and boys clocked in for the day shift at the Hulton Colliery, and most had descended the shafts below ground before 8 AM. One of those arriving for work early that morning was a 16-year-old boy, Joseph Shearer Staveley of Westhoughton, on his very first day of employment in the Yard mine workshops. A total of 347 men, including Joseph, had descended down the No. 3 pit shaft to work in the Yard mine that morning, when suddenly, at 7:50 AM there was a tremendous underground explosion, about 300 yards deep below the earth’s surface, at the level of the Yard mine.

Mr. Alfred Tonge was the General Manager of Hulton Colliery at the time, and he lived almost two miles away from the pit head. He was home at the time of the blast and heard the explosion. He immediately left his home and arrived at the mine within about twenty minutes, leading a team of rescuers into the mine. He wrote an account of what he found upon his arrival, which was turned in to the inquiry as evidence during the investigation.

Only 4 men working the Yard mine that morning were fortunate enough to survive the initial blast. However, it is likely that if Mr. Tonge had not acted as swiftly as he did, that these young men may not have been as fortunate. The initial survivors of the blast were Fountain Byers, John Sharples, Joseph Staveley, and William Davenport. We know from the diary entries of Fountain’s brother, Ben Byers, that Fountain would survive less than 24 hours. He left behind a wife, and child, just three days before Christmas, and was laid to rest at Wingates Parish Church on Christmas Day.

Two days after the accident, Joseph Shearer Staveley was interviewed by the Times and gave the following account of his ordeal in the Yard mine.

The Times

December 23, 1910

The Lancashire Pit Accident – Three Hundred and Twenty Lives Lost

There is no reasonable doubt that more than 300 lives have been lost in the disaster at Pretoria Pit.

“There is not a single shadow of hope that there is a man in the pit alive,” said Mr. Gerrard, the Inspector Mines. Rescue parties were in the pit all night, and they have been working ceaselessly throughout the day, but they have seen no sign of life or anything that could lead them to suppose that life could possibly be supported beyond the area of their investigations.

When the exploring party returned to the pithead at 3 o’clock this afternoon Mr. Gerrard announced that they had almost arrived at the coal face, and had found an accumulation of afterdamp and gas which stopped further progress and proved that nobody could be alive in that district.

It was thought yesterday that none of the men who descended into the Yard Mine in the morning had been brought out alive. It has, however, been discovered today that one of the 440 men who were brought out by the Arley shaft was in the Yard Mine when the explosion occurred. He is a lad of 16 years, named Joseph Staveley, and it seems only too clear that he is the sole survivor of the actual catastrophe.

The boy told me the story of his escape at this home at Chequerbent this afternoon. It was in the following words:

“The fitter to whom I was apprenticed, James Berry, and the under-manager, Mr. Rushton, and I went down to the mine at 7:30 AM. The fitter and I went down to the pump house about 200 yards away from the bottom of the Yard shaft and 100 yards from the Arley Mineshaft. We had just got into the pump house when the explosion took place. It sounded like a cannon going off. It knocked me to the ground, but the fitter kept his feet. We made our way along to the Arley Pit when the fitter fell, and I fell over him. We had smelt the gas very strongly. I lay there, I think, for about an hour. When I woke up I found that the fitter [James Berry] was dead.”

“I made my way up to the Arley Pit and shouted for about an hour. About 10 o’clock a party came down. I saw nobody else alive in the Yard Mine, and I did not think that I should be saved.”

There was very little change in the aspect of the pithead today. There was again a large and silent crowd on the colliery embankment, but there was little for them to see.

Now and again a rescue party of six with its goggles and breathing equipment would step into or out of the cage. It was noticed that the leader of each party carried a cage with a bird in it. The first few birds which were brought back to the surface were alive. At length one was seen to be dead, and that little incident exercised a singularly powerful impression on the minds of the onlookers. It brought vividly home to them the difficult nature of the rescuers amid the foul and heavy air of the mine and showed how illusory was the hope of finding any of the imprisoned men alive.

The real picture of the disaster is to be seen not at the colliery but in the neighboring townships. Every other house at Chequerbent and Wingates had its blinds drawn today, and few families have escaped losing one or more members.

A Wingates family has lost the father and five sons, and a Chequerbent family has lost the father and three sons. The last case has a peculiar pathos, as the youngest son was making his first descent into the mine.

Article From Staveley Genealogy